Labor-intensive manufacturing has limited the use of lighter, stronger composites but that may change with emerging techniques

There have been only a handful of ages of new materials in the history of humankind—ceramics, steel and plastics come to mind—and we are now on the cusp of the next one: composites. When we talk of composites, we’re speaking about such things as the carbon-fiber ones in wind turbines, race cars and the Boeing 787. Such materials have the advantage of being far lighter than the metal parts they typically replace, while being just as strong, and requiring fewer resources to make.

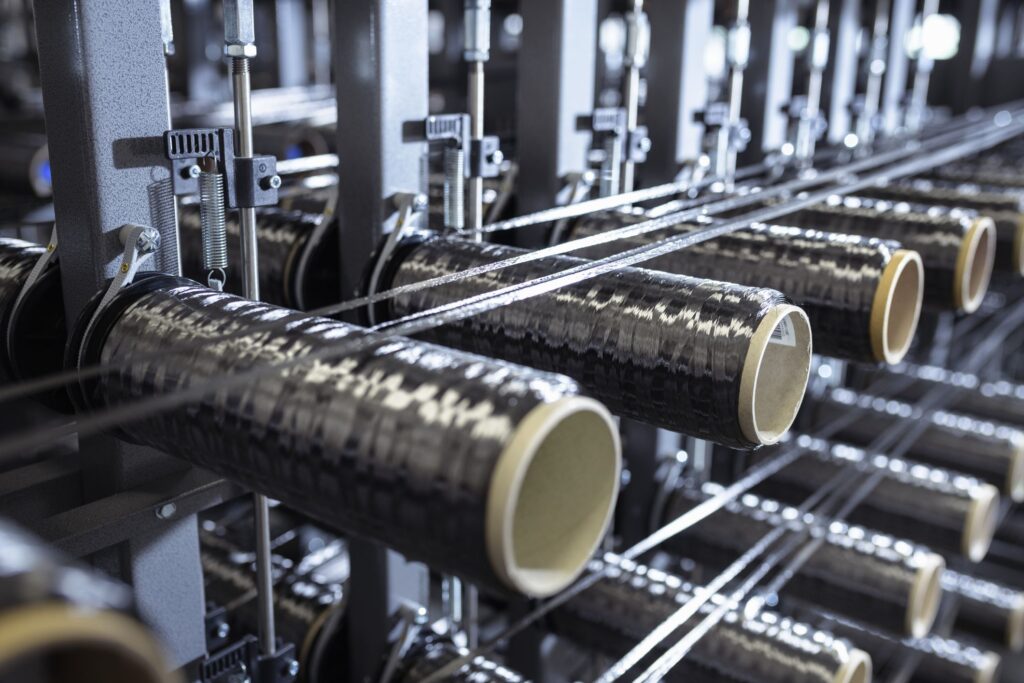

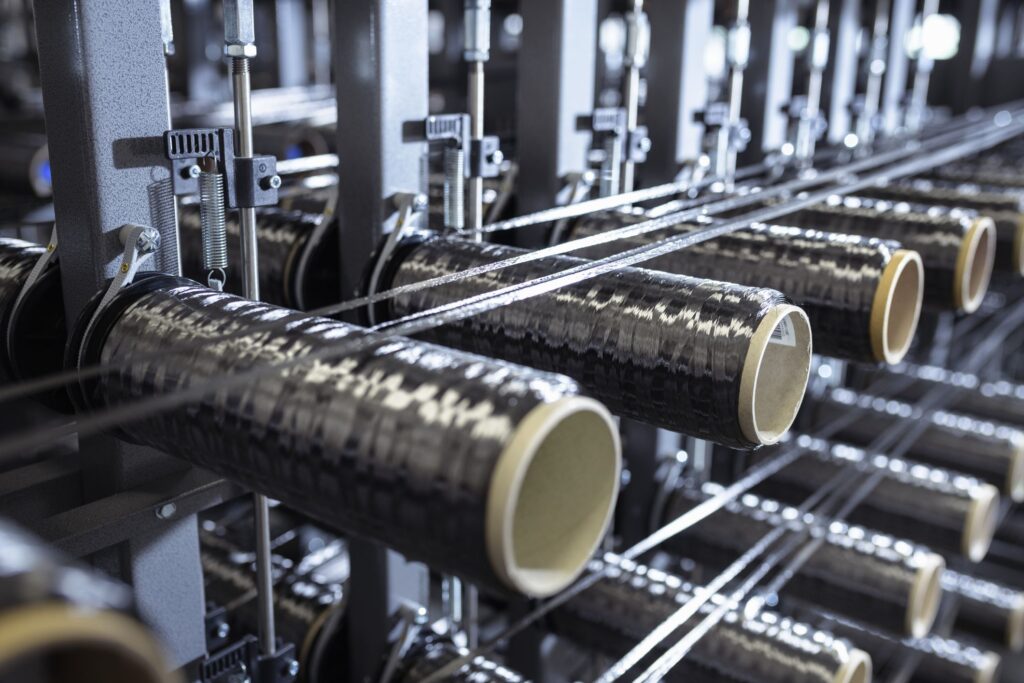

Materials scientists have had limited success making composites affordable and accessible for decades, or possibly millennia—technically, they were invented by the Mesopotamians. The labor-intensive nature of their manufacturing has made them expensive, which has limited their application to a handful of areas where their advantages outweigh their costs, such as the aerospace industry. Now, thanks to new manufacturing techniques that can churn out composite parts quickly and cheaply, all of that is changing, and the results could be both profound and exciting.

Modern composites, starting with Bakelite, were pioneered in the early part of the 20th century. Other composites were invented at a steady pace, and the industry began to hit its stride in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when automated processes for turning things like carbon fiber into giant structures like airplane bodies and windmill blades reached maturity. In just the past couple of years, a number of startups have developed processes for creating all sorts of small objects from composites, in a way that is fast and inexpensive. These include Berkeley, Calif.-based Arris Composites, 9T Labs in Zurich, Orbital Composites in Silicon Valley, and others.

Shifting substantial portions of what we make and use from steel and plastic to composites—which are amalgamations of a variety of fibers, embedded in a variety of plastics—could bring new kinds of transportation, more terrifying weapons of war, and lighter and more durable smartphones, wearables and other consumer electronics. All of that is possible because composites, while they have their challenges, are often able to perform just as well as high-strength metal parts, but with a fraction of the weight. Composites are the reason modern jetliners are so fuel-efficient, and the entire wind-power industry would be impossible without enormous turbine blades made from composites.

It’s one thing to make airplanes out of composites—Boeing pioneered this technology with its 787, on which nearly every visible surface is in fact made of a carbon-fiber composite. It’s quite another to mass-produce smaller composite parts of the kind that we typically make out of titanium or other metals, such as the bolts and brackets that hold a 787 together. As with other pioneering manufacturing technologies, such as 3-D printing, bringing composites into the mainstream is more of an evolutionary process than a revolutionary one.

Today, you can buy consumer products made with ultralight, ultrastrong parts from Arris and 9T Labs, including Brooks running shoes, spokes for bicycle wheels, and luxury watches. But what’s coming is even more interesting: Arris’s technology is being tested by Airbus to replace metal brackets inside its planes and by Singapore-based ST Engineering, which performs a substantial fraction of the repairs on airplanes in the U.S.

Olympians, including Dutch marathon runner Abdi Nageeye, are using a new tool they hope will boost their medal chances this summer: tiny monitors that attach to the skin to track blood glucose levels. Continuous glucose monitors, or CGMs, were developed for use by diabetes patients but their makers, led by Abbott (ABT.N) and Dexcom (DXCM.O), also spy opportunities in sports and wellness. The Paris Olympics, which start on July 26, are an opportunity to showcase the technology – even though there is as yet no proof it can boost athletic performance. “I do see a day where CGM is certainly going to be used outside of diabetes in a big way,” said Dexcom’s Chief Operating Officer Jacob Leach. Diabetes patients remain the CGM specialist’s commercial focus, he told Reuters, but Dexcom is also working with researchers on future use to optimize athletic performance. He would not disclose details.